“Trump’s trade war with China hasn’t wrecked Tech – yet”.

In September 2019, at the height of the US China Trade War, Wired wrote an interesting article , observing that the Trump administration’s move from 10% to 25% Tariffs on Chinese goods had not yet resulted in a full scale downstream impacts to the global supply chain.

I spent time looking at the data, and my take is: now, it definitely has.

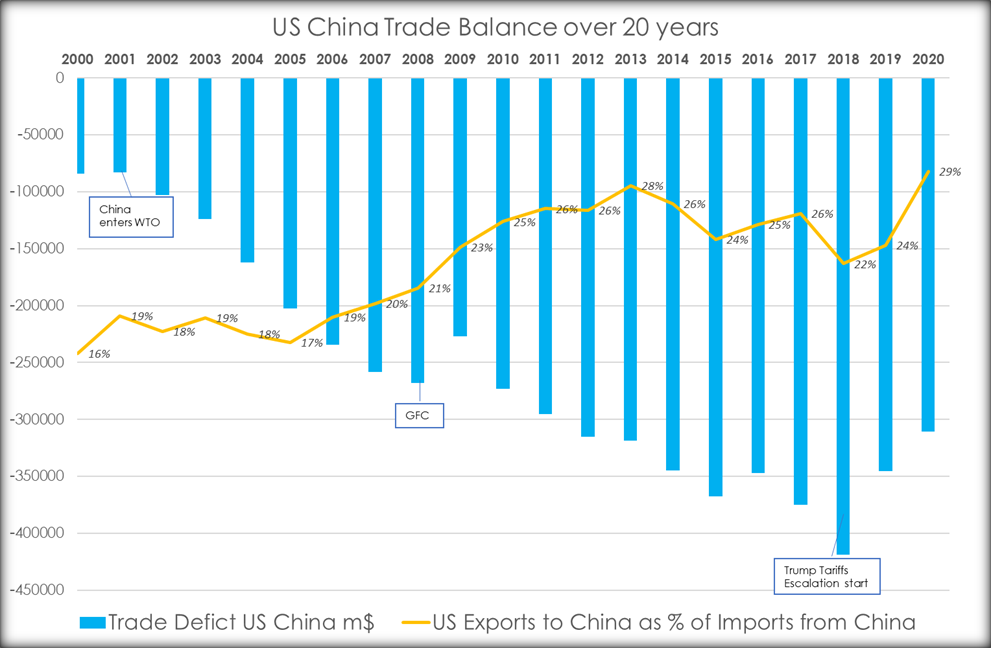

yFirst let’s look at the overall trade balance US – China.

As a matter of fact, since China joined the World Trade Organization, the trade volumes as well as the trade deficit on the US side has multiplied by a factor x5 , at the same time as the Chinese economy inevitably became the second largest.

When President Trump released the waves of tariffs on Chinese imports in early 2018, instead of reducing the deficit right away, the US trade deficit reached its worst at a staggering -$418 BILLION.

The percentage of US exports vs US imports from China dropped as well, with China exporting $500 into the US for every $ 100 coming from the US into China.

This trade deficit got a little better by end of 2020 as China resumed purchasing American oil and soybeans but the trade deficit is still at large and above a solid $300 BILLION in favour of China. This is equivalent to the total GDP of [Ecuador + Kenya + Croatia + Uruguay] combined, to give you an idea.

What this trade war has done however, is open a whole new can of worms on the global supply chain, and we are only starting to understand how far down the rabbit hole this goes.

Here are some examples:

- Financial Times reported that the temporary lay-offs announced early Feb 2021 at major automotive companies including General Motors and Ford in the US have now been announced to become “indefinite” in some of their flagship US plants.

- The IT Wire reported that The NBN Co, the company rolling out Australia’s national broadband network, announced early Feb 2021 it will stop providing new connections on its HFC network, due to an acute shortage of network termination devices, impacting internet service providers ability to deliver essential broadband service.

- The NY Times reported that, the surge in worldwide demand by educators for low cost laptops had created major shipment delays, and pitted districts and schools throughout the US against one another for shipments of computers. In fact, the shipment of PC units and Chromebooks in the US in 2020 surged at +15% vs 2019 according to Gartner, but this was scarred with long lead times and considerable extra costs to fly the units into the country. The collateral damage were the many thousands students from lower income families who started remote schooling with no device (or only sharing a mobile phone). The resulting “digital learning divide” can not be underestimated.

I experienced these bubbling issues first hand when I ran a global sourcing event for a customer in Australia last year for a 5000 premium laptops business – what would be considered an attractive volume in different times. What happened instead was that most OEMs politely declined and directed me to local distributors. The Victorian government had just ordered 250,000 laptops, and in truth, finding 100 machines was in itself considered a miracle.

What these examples have in common is that they all require something most people normally couldn’t care less about: tiny little things called semiconductor chips. And currently a global shortage of these integrated circuits ranging from processors, controllers, memories, display drivers is hitting industries that need them badly.

Take the example of a car.

40 years ago, the inside of a car would look like this:

A beautiful mix of mechanical, hydraulic, and electromechanical, with at its core an engine, a distributor or alternator, and a carburetor. Good old engineering!

One could open it, and with a bit of experience and wits, fix some of the most common issues.

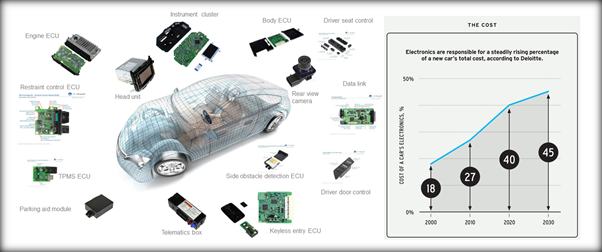

Nowadays, the inside of a car resembles more a network of computers on wheels really. It’s estimated a premium car has 100+ electronic boards embedded, each board with its own microprocessor, controllers, memories etc.., all connecting to the main computer through a common bus. This means that the share of electronics cost into the total cost of the car is anywhere between 40 and 45% according to Deloitte.

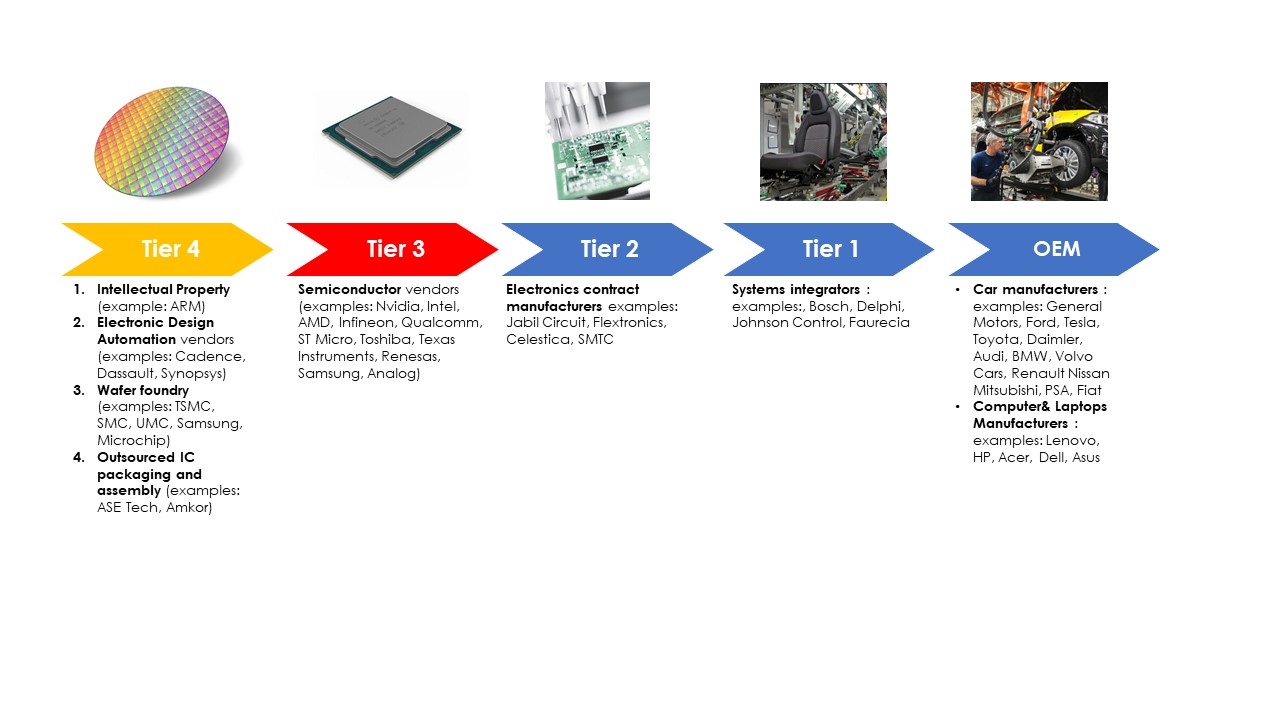

The value chain of that 40% is a lot more complex, global and interconnected that people may think. I put together this simplified view, based on my 10 years experience as Procurement practitioner in that industry.

)he red and orange are where the supply chain pain points and bottlenecks are being felt currently, with semiconductor vendors unable to meet the huge demand due to three main factors:

1. The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in steep sales decline in the automotive industry in 2020. This led the semiconductor vendors to switch their production to other customer industries, such as consumer electronics and computers, where the demand skyrocketed instead. This is especially the case for more profitable lines of products in the gaming / high performance CPU segment. In the meantime, some of the car markets have recovered significantly, especially in China. Guess what: the capacity is gone and lead times are through the roof.

2. The trade war between US and China has led a number of Tier 1, Tier 2 and even Tier 3 vendors to reconfigure their production footprint and start deploying sources of supply outside PRC China (mainly South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam) in order to circumvent the reciprocal sanctions and tariffs. When the demand pent up, these investments were not necessarily live yet or not fully operational. I have personally worked on several transfers of technologies and manufacturing in Europe, Asia and South America, and in my experience, setting up and ramping up new facilities and assembly lines is in normal times a challenging project. I can only imagine how much harder it would be during a time when nobody can travel internationally to get the job done.

3. The roll out of 5G technologies has accelerated tremendously in some of the big markets, taking up Tier 4 and Tier 3 manufacturing capacity.

This issue has consequences in the real economy as automotive manufacturers are forced to shut down production lines and stand down staff. I personally find it truly heartbreaking to see a government rushing trade tariffs and sanctions as a political tool, “selling” that it will bring back jobs onshore, when it actually has the opposite effect.

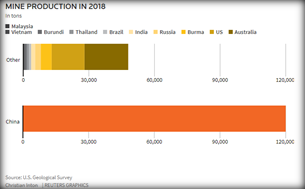

Supply chains are global and they just don’t work that way. The Washington Post reported that President Biden seems to have understood the risk and has commissioned a review of supply chain vulnerabilities. I can tell you already that beyond semiconductors and most likely PPE equipment, which are known issues, the next threat has to do with rare earth metals.

Rare earth elements are used in mobile phones, electric vehicles (required for the neo-magnets that form the core of the electric engine), military jet engines, satellites and lasers (therefore critical defence infrastructure).

Guess what: China accounts for around 80% of U.S. rare earths supply!

Australia has built up capacity in that space and will no doubt have a role to play.

This illustrates how important it is to understand and proactively manage your supply chain vulnerabilities. We at excelerateds2p do that for a living. We can help you not only understand, assess and proactively manage your supplier risk and supply chain risks, but also implement solutions to keep these strategic risks under control, to avoid them becoming critical bottlenecks that can jeopardize your whole business.

Author:

Abel Salhioui, Lead Consultant

excelerateds2p

APAC

Recent Comments